Artist Statements

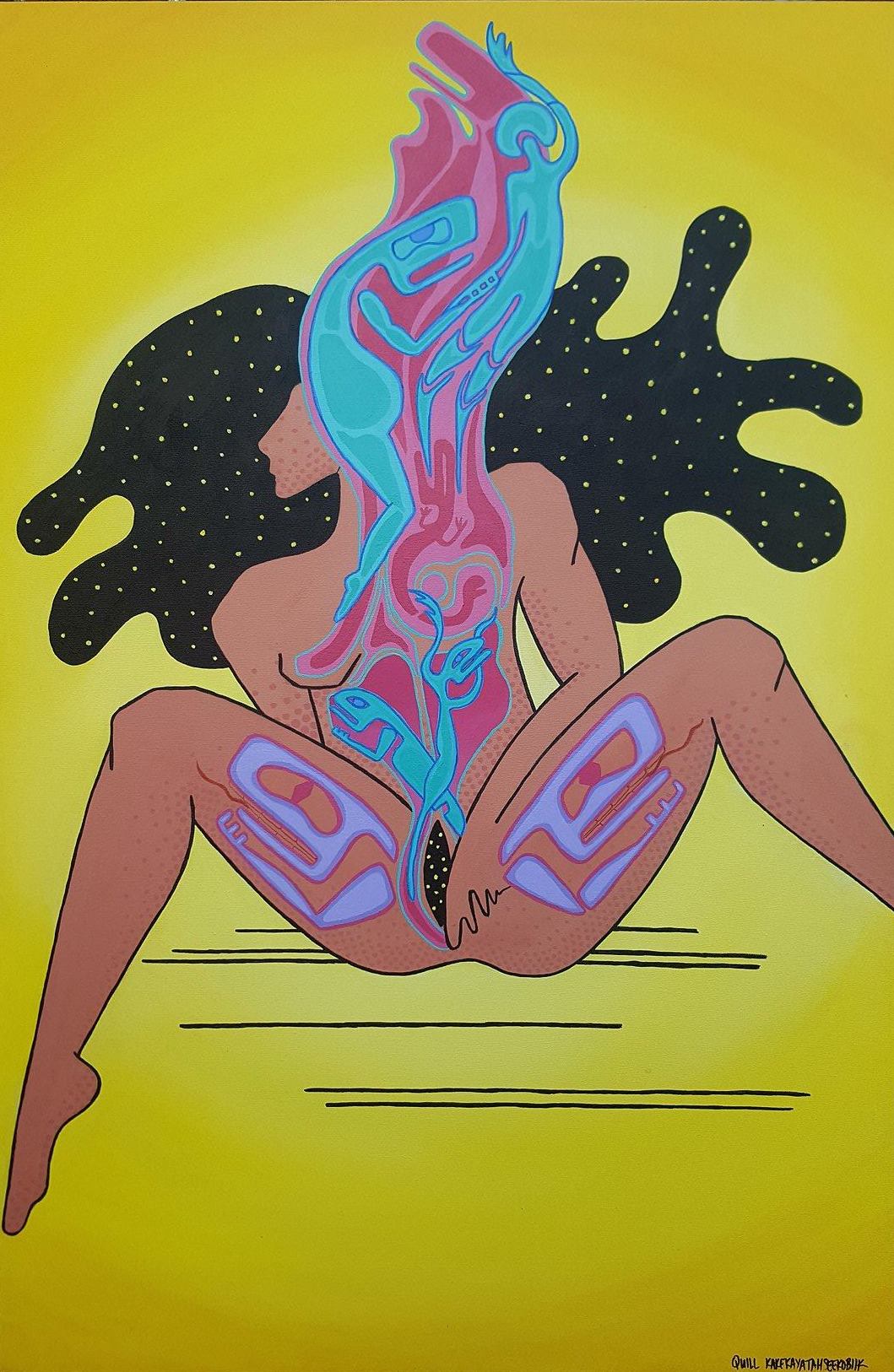

Gwen: For me, I was strongly influenced by Quill’s art. It was the first time that I saw Indigenous women’s bodies shown as sacred/powerful while masturbating and menstruating. As a trans woman, I had a complicated path to having a vagina (including surgery and hormones) so it felt really liberating to see Indigenous womanhood in connection to land, creation, ancestors and pleasure. It reminded me that the medical processes I was going through were connected to my culture and being in a profound way.

I guess I think a trans woman’s body is often seen as “fake” or somehow artificial, but my experience of my body is that’s an extension of my ancestors and still connected to the land. That my gender has always been a part of my being. Surgery or hormones was just a way to bring my body into alignment with my spirit-and it’s a beautiful thing. As well as an act of sovereignty.

The idea that a trans woman’s body or transitioning is a sovereign act may seem odd to people, but it’s rejecting a colonial violence against us (forcing us into Western gender systems) and reclaiming our inherent femininity inside culture. It’s about connecting our sexualities to our land-seeing our pleasure as also sovereign. Our bodies, our right to be loved, to feel good.

I also want to talk about sexual violence and rape because that’s also a part of my body. Being raped by a white man and caught in an abusive relationship with him really complicated my transition and my body. As I discover and form a relationship to my vagina through sex and masturbation that’s rooted in my pleasure, I have to heal from those violations-and I think those violations mimic the colonial violence which happened to my ancestors and is currently happening to the land (ie pipelines and resource extraction).

For me, healing is reclaiming that holiness (a messy truth of land, bodies, gender, sovereignty) through waterways, pleasure, and speaking back. Quill’s art is such an embodiment of those ideas that was so healing for me to see visually and connect with her. She’s just an amazing artist that I’m so honoured to collaborate with. I think we all need to see and engage with her art because it’s incredibly powerful.

Quill: I am so deeply appreciative of the places that Gwen has transported me to with her words. I first read Gwen’s work when I was completing my masters degree, inundated with political theory that did not recognize the layers of privilege it speaks from, frustrated with the lack of space for me to critically explore the concepts of resistance and decolonization through my own body as an Anishinaabekwe.

Gwen’s collection of poetry Ceremonies for the Dead, gave me the language to articulate what I had been feeling my whole life, that the body is so much more than our flesh, that linear time is a façade, that our ancestors are agentive entities that we carry in our bones and blood. Gwen’s work, for me, was the most important text I read during that time in my life, a work that was not just poetry, but that was also political theory and resistance and decolonization and resurgence and time travel and pain and love. She embodied these concepts in her words, evaded the didactic explorations of these theories that I was so frustrated with in my education, landed these explorations in the intimacy of my own body. What a beautiful gift.

During this time in my life, I was also inundated with masculinist approaches to “returning to the homeland” as the most important part of Indigenous nationhood. I always saw this as an oversimplification. Our homelands are not that simple and static. Our homelands are not just those physical places we come from. Our homelands are our bodies and our ancestors, story and song embedded in river and rock, story and song embedded in our bones and blood.

Gwen’s work so beautifully reclaims the complexity around how we conceive of our bodies and our homelands and in turn of how we conceive of resistance and love and nationhood and liberation. Returning to my homeland can mean participating in those practices that physically presence my body on the land. Returning to my homeland can also mean touching this body of mine, making myself and the places I come from feel great pleasure. These practices that return us to our bodies are deeply threatening to the colonial project. This is why I receive hate mail when I paint myself masturbating and menstruating. This is why there is no space for us to talk about our bodies. This is why I am constantly peeling off layers of shame that separate me from my body.

Returning to the body resists the genocidal intents of settler colonial sexual violence enacted on the bodies that fall outside of the bounds of cis-heteropatriarchy. It is time to dismantle the hierarchies that frame Indigenous resistance. It is time to value, hold up and make space for the labor and love of Anishinaabekwewag to remain in their bodies despite the violence that our bodies constantly endure. It is time to bask in the beautiful words of Gwen, to witness how her words are wisdom that emanate from her body and her ancestors and her homelands and the great beyond. What a beautiful gift.

Gwen Benaway

Quill Christie-Peters

My body. You have sat by a swiftly flowing river for 26 years now, sifting through the rushing water, sifting through the flow of this universe around us, running your slender fingers through the ripples of creation that pass us by. You are muscular and lean, beautiful and brown, hands etched and weathered from the work that you do, wrinkles around eyes that form when you chuckle deep into belly. You sit in silence and catch fish by the river, ever so carefully place them into a basket. You softly float above the ground, travel around our homelands to harvest berry and medicine.

My body. You return to sit by the river in unfaltering diligence, your eyes scan the water’s surface looking for the moments in time that you must catch, the moments in time that kwe cannot bear to catch herself. Ahh, there are so many moments. You dig a hole without pause in the moist earth of our homelands, planting these moments in earth that is bone, saving these moments in the memory of body.

My body. When night falls, you tend to fires that I can feel warming my lower belly. You sweat with the labor of collecting these moments for me. You scream in anger because these moments are so intentional and you have seen them before. A single tear falls from my eye while I am trying to shop for groceries.

My body. You are the gathering place, the sacred threshold. When night falls, you invite all of our ancestors to feast under the bright moon. You direct these ancestors around the broken earth where you have buried these moments and they sing and drum, eat and laugh. They invent ceremony in the darkness to sing these moments into growth and a single green stem shoots up from where these moments were planted.

Sometimes, the ancestors must come for months and years on end. Without hesitation, you welcome and feed them. Sometimes, the ancestors must summon our spirit relatives and kwe wakes up suddenly in the night with the feeling that she is not alone in her bedroom.

My body, you have always been the ceremony to transform pain into creation, the gathering place of all our ancestors and spirit kin. My body. Our oldest Anishinaabeg technology. My body. Our oldest Anishinaabeg technology.

I sit here now, thinking of you. I am in a coffee shop and I am frustrated by the way that my body is under constant surveillance in these public places. But I guess the huge sticker on my laptop that says THIS IS INDIAN COUNTRY doesn’t help, the tattoos that trace my lineage to this place an uneasy reminder to onlookers that they do not belong and the way that I appear to move through spaces comfortably and with confidence threatening to their sense of ownership over space and land and home. They tell me with their eyes that I don’t belong. They make me work just to sit here. Some days, I stare right back. Some days, I choose not to sit in that coffee shop, choose to be away from the exhaustion of moving this body through space.

When I think of you, my dear body, I first see stars. When I think of you, my dear body, time falls off of my shoulders like a silk scarf. I am young kwe, the one who knows without question to listen to the ancestors murmur in the night, the one who sits with you for long afternoons on end, the one who understands you create the boundaries of space I experience and are both the upholder and bender of time. I have always known you to be ancestors and drum and river and rock, stardust exhaled by heavily breathing spirits in the great fog. You are mine but you are not. You are me and you are them. You are this flesh and you are all of creation. My body, I have always known this.

I want you to know that you have saved me many times. They beat and rape language from our tongues and yet you saved this language in my bones. These beautiful bones you have given me echo with the voices of ancestors who sing and whisper sweet Anishinaabemowin when you invite them to feast by the fires in my heart. They took the language from my mind but it is still the language of my body. I want to thank you for the seeds you save in my flesh, the way my hands remember when I bead and paint, harvest and make, the way my mouth relaxes when I speak Ojibwe. When the spirits greet us kakekayatahseekobiik,never ending light, what was thought to be lost can always be found in us. My body, you have always taught me that I am not alone and I want to thank you.

When I was ready, you showed me the reflection of my parent’s bodies in my own. Young kwe traced the lines of violence across the contours of her soft flesh, was given the gift of understanding the behaviors of those I love by charting their histories on my own skin. Beyond those bodies that created me, the bodies of all my ancestors extending onto a great horizon that I can visit through my own flesh. My body, you are the structure of how I experience this time and space, but you are also the exit out of it all. You took me to visit all of the bodies I come from, to carefully look at the ways they have been bloodied and bruised, loved and cherished. What a painful gift. It hurts so much to look at what they’ve done to us. That school. Those moments. All of those relatives and their bodies. Piled onto mine.

The anger builds up in you and I from time to time. They talk about reconciliation but foreclose any spaces that allow us to feel whole. After the residential schools, a generation was created that invented new ways to accept and process broken love. Even as small children, we recognized genocidal intent, carefully charting our realities in alignment with this colonial project, shapeshifting and dancing around our parents’ broken bodies so that they could feel a little more loved, a little more whole, even if that meant sacrificing parts of ourselves that needed that love reflected back to us. Us Anishinaabeg always inventing technologies to resist. Us Anishinaabeg, intelligent power beyond their wildest dreams. They didn’t realize that even children are ancestors and homelands and spirits and dreams, that we always have the ability to call on the knowledge we have stored away in our flesh since time immemorial.

I lean back into this big leather couch at the coffee shop. I’ve fought so hard to return to this place only to feel the racism coating my body as I move through this city, only to witness how white supremacy reigns astonishingly overt in these institutions. This city makes our bodies extra heavy. I am love-filled, gentle, gracious and generous Anishinaabekwe. But in this city there is no room for Anishinaabekwe love because that love demands sovereign space and deep accountability and ceding control over our communities that are bounded by the violent structures of colonialism. And so, I become a harasser, deviant, probably someone who will be pushed out of opportunities in this city, simply for the love that spills out of my body. I swim in a sea of normalized white fragility. In this city, white supremacy has built strong walls around itself made out of white women tears, angry Indian woman tropes, broken and bloodied Anishinaabe bodies, broken and bloodied Anishinaabe homelands. And yet, we persist.

My body, I want you to know that I am sorry for the times that I abandoned you.

It started to hurt when I couldn’t protect you. Hands touched my young body and a barrier was created between you and I. Softly, I drifted away from you in a hazy fog. Settler colonialism is liminality, a cold and still place that our minds and spirits escape to in order to take a break from the violence our bodies endure. I have danced in this liminal space, have lingered a moment too long, wondering what it would be like to leave you for good. My skin is the boundary from this world to the next, our ancestors waiting on the other side of flesh, the side closest to our hearts. Sometimes, I want to tear myself open to be with them. My body, you have always been so gentle with me, softly calling me back, never shouting, never shaming. My body, you have always kept these moments that I could not bear to look at, showing me them when I was ready, calling the ancestors in to sing these moments into creation. My body, you and I know it is okay to struggle, it is a sign that we see what is going on.

It still hurts to touch you. I still cannot sit with you for long afternoons like young kwe used to do. But, now I understand. They try so hard to stop us from tracing the lines and ridges of one another, from mapping the stars and bodies and places we come from together, from realizing our ability to exit time and dance with our ancestors through our bodily technology. They try so hard to push me into liminality, muted and numb, so that I travel far away from you. They do this so that my love cannot overflow out of hands and heart onto the bodies of my community and my homelands, so that this love softly recedes into that liminal place of stillness and nothingness. My body, you have told me that you are home and stars and blood and river and sweat and dirt. You have whispered that you are resistance and love and I have listened.

My body, I want you to know that I love you with everything that I am. This love is not perfect, it is messy and complicated and painful and beautiful, but it is love nonetheless. I am sorry it took me so long to tell you that I love you. I am sorry that I know that I will not be able to tell you that I love you every day. I am sorry that I will likely dance between your warm embrace and that cold space of liminality time and time again. But my body, the love between us is not a practice or a feeling but the medium in which you have grown me, it is that river that you sit by as you listen to my beating heart, it is the moist earth of our homelands that you plant the seeds of my trauma in, it is omnipresent ancestors’ voices and laughter. This love does not abide by linear time, it is the deep exhale from the great beyond, the soft voice that has called me back to you from liminality, the soft voice that has called me back from leaving you, the soft voice that has called me back from the times I have harmed you. My body, you have fostered and tended to this love since time immemorial in our bones and in our blood, it is that which always remains, that which will always be. Our greatest Anishinaabeg technology.

It is now that I understand that every touch, every gentle stroke, every ounce of pleasure that we share together, a resistance so profound that my relatives sit a little straighter in their quiet homes, a colonizer awakes in the night with nightmares of his empty and meaningless life, a white woman is forced to confront the violence she enacts on Anishinaabekwewag who spill their love onto all that they touch. Every moment spent together, a resistance against that liminal space, a tending to the fire that unites kwe with her ancestors, a healing drop of water that sends ripples into the great beyond. Every ounce of pleasure we share, dear body, a resistance so profound that those stars we come from rumble and shake, a river of creation descending and blanketing the earth.

I will always return to the coffee shop and to the many spaces in this city where I laboriously exist, walking confidently by those that scowl and question me with their eyes, learning to collect racist encounters into a glass that I will then drink to sustain me. I will always take up space with honor and grace, despite being called a harasser, despite the tears that I never get to cry, my love always spilling out of me, drowning the white supremacist gatekeepers that bound our bodies and lands. And I will always, always, touch myself under the full moon, dancing with my body around a sacred fire where my ancestors laugh and feast, fingers bloody with the knowledge us Anishinaabeg have tended to since time immemorial.

My body, you have always been the ceremony to transform pain into creation, the gathering place of all our ancestors and spirit kin. My body. Our oldest Anishinaabeg technology. My body, the greatest love I will ever know.

Nice

LikeLiked by 1 person

I am simply blown away by the beauty of this writing. We could all wish to know our bodies so well and create such an intimate relationship with it. I am in deep gratitude for your sharing; you have opened me up to a way of learning from myself— thank you! thank you!

LikeLiked by 2 people

[…] Teaandbannock. “Decolonial Love Letters to Our Bodies – Gwen Benaway and Quill Christie-Peters.” Tea&bannock (blog), April 28, 2018. https://teaandbannock.com/2018/04/28/decolonial-love-letters-to-our-bodies-gwen-benaway-and-quill-ch…. […]

LikeLike

[…] https://teaandbannock.com/2018/04/28/decolonial-love-letters-to-our-bodies-gwen-benaway-and-quill-ch… […]

LikeLike

I really enjoyed the works displayed here, along with the poetry and story. I felt both of your feelings and heart poured into these pieces about decolonizing the body with love. Your artistic expression portrayed within these works are profound and I felt the overwhelming feelings that came within it. Intimately expressed and beautifully written!

LikeLiked by 1 person