I have nothing but mad respect for Chief Lady Bird as an artist and friend. During my travels in Toronto earlier this winter, I made it a point to go see her at an art & craft fair, and she was amazingly open to me being all “I like your work, be my friend.” I had first noticed her work last year, and was hoping to have her on as a featured artist, so I’m extremely happy this all worked out.

Introducing the eva-talented, Chief Lady Bird…

1. If you could collaborate with one other artist, who would it be and why?

Outside of the collective of artists that I currently collaborate with (Aura, Chippewar, Mitch Holmes, Reagan Kennedy, Nyle Johnston), it’s been my dream to create a mural with Christi Belcourt and Isaac Murdoch (Onaman collective). The murals and street art that I do with Spirit Arts Collective is very aligned with Onaman Collective’s art initiatives that connect youth to the land and the language. We all have very strong voices and I can see a collaboration being very powerful, unifying, and full of meaningful dialogue.

2. What is your favourite piece to date, and why?

My favourite piece is Medicine Man. It was the last piece I created during my thesis at OCAD University and features my dad. On the day I took the photo, we took the boat out on Georgian Bay to Tadenac where our ancestors are buried. We did ceremony and I was able to capture the essence of the smudge through silhouette and digital manipulation. I love that this piece combines storytelling with painting and bead work to discuss connection/disconnection to the land and our languages, and the importance of ancestral connection… concepts that we can all relate to as Indigenous people. It’s a very special piece. It’s one of those pieces that accesses one of my personal experiences to talk about ideas and issues that affect us all. And I think all of our individual narratives are essential to the greater narrative of who we are.

3. What does working in schools with the Youth mean to you, and how is that reflected in the murals?

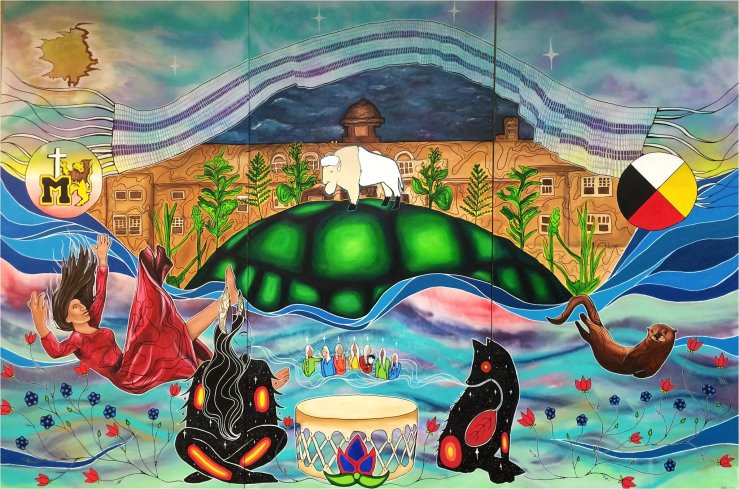

Creating murals in schools is one of the most fulfilling aspects of my career as an artist. It’s hard as hell because we open wounds when we speak hard truths and address the internalized and systemic racism that continues to exist within formal educational institutions. We address all of this while also teaching technical painting skills and painting on the mural ourselves. It can be exhausting but I love it. I love working closely with the students and hearing their stories. I love being able to find new ways to engage the students (which usually means using my tattoos as a teaching tool) and decolonize their education. I love watching the students enter the project rather timidly and then gain confidence throughout the project. There’s a lot of growth that happens when we create murals in schools. We ensure that our students receive an honest education about Indigenous peoples; we include traditional teachings, historical facts, contemporary issues, and personal narratives to create strong, trusting bonds with the kids we work with. One of my most favourite parts of mural creation is when an Indigenous student comes forward and opens up about their identity because they feel safe. There were a few students that Aura and I worked with recently who had never talked about it with their teachers. Because they felt safe enough to tell us, we were able to provide that information to the school and establish a smudging area at the school so these students could connect to their heritage. We are able to reach kids on a creative, collaborative level and this type of immersive learning is most effective because it shakes up the normalcy of Western pedagogy. The murals that we create with students bring our worldviews to life and invite them in, creating a safe space where we can all learn together and have fun.

4. What has been your favourite mistake, in terms of your art?

My favourite mistake was assuming I was in this alone. It has been such a pleasant surprise to realize that we, as Indigenous artists, have such a strong community to work with. There was a certain level of fear when I thought about taking on a career as an artist because I thought it would be very cut-throat and I’d be working alone. But I am fortunate to be working with so many amazing collaborators who are strong, unwavering, loving and hardworking. Teamwork makes the dream work!

5. Who inspires you, outside of art?

My mom inspires me everyday. She is the glue that holds our family together. She is the strength that runs through my veins. She carries the spirit of all the women who came before us. She is strong, hardworking, compassionate, independent, honest and loving. She is one of the few people I know who truly lives by the seven grandfather teachings and she is the reason that I am an independent Anishinaabe kwe.

6. Growing up on-reserve with a parent who practiced traditional medicine, and then moving to the city to study art: can you share how you relate, or don’t relate to, the concept of “we walk two worlds?”

It’s so interesting to be asked this question because I just included this concept in a recent piece I created for Life As Ceremony magazine. Here is an excerpt:

“There’s a concept that says Indigenous people walk in two different worlds. For most of my life i’ve had each foot in a different place. It can be difficult to balance because we are often faced with questions about blood quantum, language proficiency and “authentic Indian experiences.” Sometimes, because we have our feet planted in two different worlds, we feel “not Indian enough.” I have one foot on the rez where I can smell the sage burning. My dad cuts medicines on the front step and my mom prepares a beautiful home cooked meal for when we all convene in the dining room together. Here, the walls are lined with hand drums and Nan’s birch bark placemats. As the steam rises up from our meal and curls around our faces, I prepare a spirit plate to take into the bush for our ancestors. My mukluks crunch through the fresh snow and I think about Toronto, where my other foot is planted. I pass underneath naked birch trees and imagine they are the skyscrapers of Bay Street. The peeling bark hangs solemnly like a man in a suit, hunched over and gazing out his window at the rest of the city below him. There is a dignified sadness to the way the bark slouches and I can’t help but stare. As I lower the plate to the rock where we make our offering, I am struck by how different my worlds are. I think about how when I am home up North, I feel grounded in my traditions. I think about how I can pick cedar from a nearby tree and boil it up. I think about how my dad brings his turtle shaker into my room at night, as a form of comfort and protection. I think about how my brother rides his snow mobile down to the lake and drills holes in the ice to catch bass. And then I think about how practicing our traditions in an urban space can create tension. I think about when I smudged at a friend’s house on Pape Avenue and her neighbour texted to ask about the smell, which they described as a chemical burning. I think about how people on the subway reach out and grab my medicine pouch, because to them, it is a tactile piece of history, something that doesn’t quite belong. I think about the holes that form in the bottoms of my moccasins from walking on pavement, and the ache in my feet from being so disconnected from the land. And I think about a lady in Guelph who approached me while I painted a mural. She said: “Oh, when I heard they were doing an Aboriginal mural I assumed they would have hired an Aboriginal artist!” “I am,” I said. “How much?” she replied. Arguments about blood quantum, language proficiency and “authentic Indian experiences” aside, all I can say is, I am. No matter where my feet are, or what is above me, I AM.”

7. Dreaming big, what is the ultimate goal for you, as an artist?

The ultimate goal for me as an artist is to have a gallery where we can showcase youth artists, emerging artists, and established artists. It will be a place to show and sell a diverse selection of Indigenous art, with no limitations. It will also have a studio space in the back for our collective to work, and a workshop space upstairs where we can host our own workshops or bring in third parties. It will be a social space where everyone can learn and have fun. I think that’s all I ever want is to spread the love, uplift our youth, create safe spaces and collaborate!

8. One of your latest art features Evan Adams as his character Thomas Builds-the-Fire. Which is hella awesome. Can you share how this piece came to be?

I had so much fun making this piece! And Evan Adams even retweeted it! As if! This piece was created to accompany another illustration I did, which features Kawenn áhere Devery Jacobs’ character Aila from Rhymes For Young Ghouls. Both pieces represent Indigenous film and the ways in which these characters empower our communities. I wanted to create a diptych of these characters because they represent two different eras of Indigenous film. Thomas Builds-The-Fire has been essential to Indigenous film because his character has always emphasized the importance of storytelling and oral tradition, from a humorous position. And Smoke Signals as a whole is iconic because it responds to the misrepresentation of Indigenous identity in the media and allows us to sit at the same table as “everyone else” while also acknowledging our fundamental cultural and political differences. And then we have Aila in Rhymes For Young Ghouls, who represents our youth who have to fight for their lives. Her character speaks to the crisis our youth are constantly undergoing and this film, in my opinion, is a story of survivance, which Gerald Vizenor describes as a “renunciation of dominance, tragedy and victimry.” Aila fights back, and I love that about her. Aila and Thomas are different, but both are essential to the diverse and accurate representation of Indigenous people and our experiences within the media.

9. What is something people don’t generally know about you?

People don’t generally know that I have a deep appreciation and fascination for Lady Gaga. I don’t know what it is, but ever since her first album Fame I’ve been attracted to her image and music. And the weirdest thing is that each album is released during crucial transitional phases of my life, and each of them speaks to what I’m experiencing and becomes the soundtrack for each phase. Its weird. But I’m okay with it.

10. Favorite quote:

“Yes, Pete, it is. Actually, it’s pronounced “mill-e-wah-que” which is Algonquin for ‘the good land’” – Alice Cooper, Wayne’s World Social Media:

Keep in Touch:

FB: Chief Lady Bird Art // Insta: @chiefladybird

Twitter: @chiefladybird // Tumblr: Chief Lady Bird Art Tumblr

Chief Lady Bird (Nancy King) is a Potawatomi and Chippewa artist from Rama First Nation with paternal ties to Moosedeer Point First Nation. Her Anishinaabe name is Ogimaa Kwe Bnes, which means Chief Lady Bird. She completed her BFA in 2015 in Drawing and Painting with a minor in Indigenous Visual Culture at OCAD University and has been exhibiting her work since she was fourteen years old. Her current series of work uses “beaded glyphs” as fragments of made-up visual language that reference both wampum belts, syllabics and petroglyphs as a way of understanding the loss of language through Canada’s genocidal legacy and continued assimilation tactics. These beaded glyphs convince the viewer that they mean something and create tension and frustration between the work and viewer, to emulate the frustration that many Indigenous nations feel who aren’t fluent in their traditional languages.

Wonderful Post, Thanks!

LikeLiked by 1 person