The moment I realized I was Black and Indigenous was a defining one. It was my first day of Kindergarten in the small all-White town of Shellbrook, Saskatchewan. My hair hung to my waist, parted in the middle and tightly braided. Brand new clothes and shoes were still stiff. My Aunty Joanne walked me to school holding my nerves tightly because my mama, a single-one, was a nurse who worked in the city, an hour’s drive away. My mama hitchhiked every day because we had no vehicle and “…be damned if she was going to go on welfare.”

I remember looking at the classroom and seeing a sea of faces: not one of them looked like me. It didn’t stop. Story time after story time, from Mr. Mugs to Dick and Jane, nothing of myself or my family was reflected. I was about 3 years old when I first noted how stark, or maybe the right word is how “dark,” my brown skin was in relation to the townspeople. At one point, I even caked white soap on my face and hands after trying to scrub my skin clean – it didn’t work, it just stung almost as much as the words did. I knew words. I began to read at around the same age as I began to note skin colour. My mama left me comics and other books as a consolation to her frequent absences. I was “bright as a whip,” my Grampa used to say. None of my abilities or gifts were to matter at school.

When the teacher asked us to share a bit about ourselves on that first day, I talked about books, the bush, and my Cree mosôm and kôhkom, two of my favourite people. One kid was all it took. He pointed and laughed and called me the N-word. I’d heard that word from adults, but I didn’t fully understand. Another laughed and said she’s a N-plus-an-S-word: a “N-S.” I didn’t know the S-word, it was new, but the tone and ugliness wasn’t. I felt my eyes swell and cheeks burn. The teacher never said a word, sending me to the “resource room” where I would have to go every day from that point on. The same kids with their older brothers beat me up after school on the way home.

I ran home crying, hair pulled out, new clothes all dirty, asking my Granny what those words meant. She said, “Because you’re Black.” Still in tears, I responded incredulously: “Why didn’t anyone tell me?” There wasn’t a hug or reassurance – only a clip to the side of my head and an admonishment to stop being such a fool. I grew up believing my Granny hated me. I never knew why, but there were whispers. Granny ran the “house” compromised of 12 relatives, cousins, aunts, uncles and their girlfriends included, with a steel, iron fist mostly aimed towards me behind my hard-working-but-absent mother’s back.

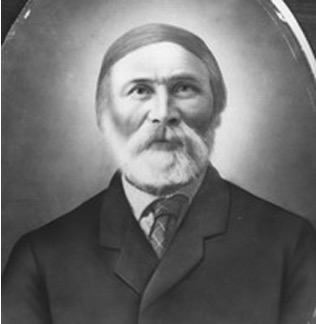

Granny, a nêhiyaw-Scottish-Metis (I leave the inflection out when referring to Scottish-Metis people) matriarch ashamed of her identity, tried to white-wash her Indigeneity right out of her skin, not by scrubbing and painting herself with soap, but by going to church every Sunday and praying her brownness out. One of her mosoms, James Isbister, was the only Scottish-Metis on Riel’s council. Because he refused to pick up arms with the French-Métis, he was shamed after the Riel Resistance and, even though he advocated against war, he was imprisoned by the British.

There were also whispers of a terrible Nêhiyaw secret. Her father told her she must never let her skin darken and ensured she was covered from head to toe with gloves, a bonnet, and a parasol. It was dangerous to be nêhiyaw or Metis/ French-Métis in the Prairies after 1885.

My Grandpa was the exact opposite. He was a brown crinkly nêhiyaw speaking tall man who wore plaid, suspenders, gum rubbers and one of those fancy hats no matter what the occasion was. He was as proud as proud could be of his nêhiyaw and Scottish-Metis ancestors, regaling me with tale after tale of men who could run so fast they would beat the train and women who knew the medicines of the land. No matter what, he carried himself with respect. One Sunday he decided to go to Church, “just to see,” he said. After the service, every single white church person refused to shake hands with him as we walked down the receiving line. I remember being so furious. He didn’t say a word though. I grabbed his hand protectively. He squeezed mine tightly and we walked straight out of there. He never went back and I vowed never to as well. “The land was our church,” he said. I remembered these words when I snuck out of the house at 6 am Sundays and headed to the bush so I wouldn’t have to go. I caught hell every Sunday evening though as I ducked hands and felt the sting of the tip of the dishtowel on my face as she muttered how “I was a Blue Beard’s daughter, for sure.” I didn’t even know what a Blue Beard was until I looked it up for this piece. It refers to a man who kills a series of women, or seduces and abandons a series of women.

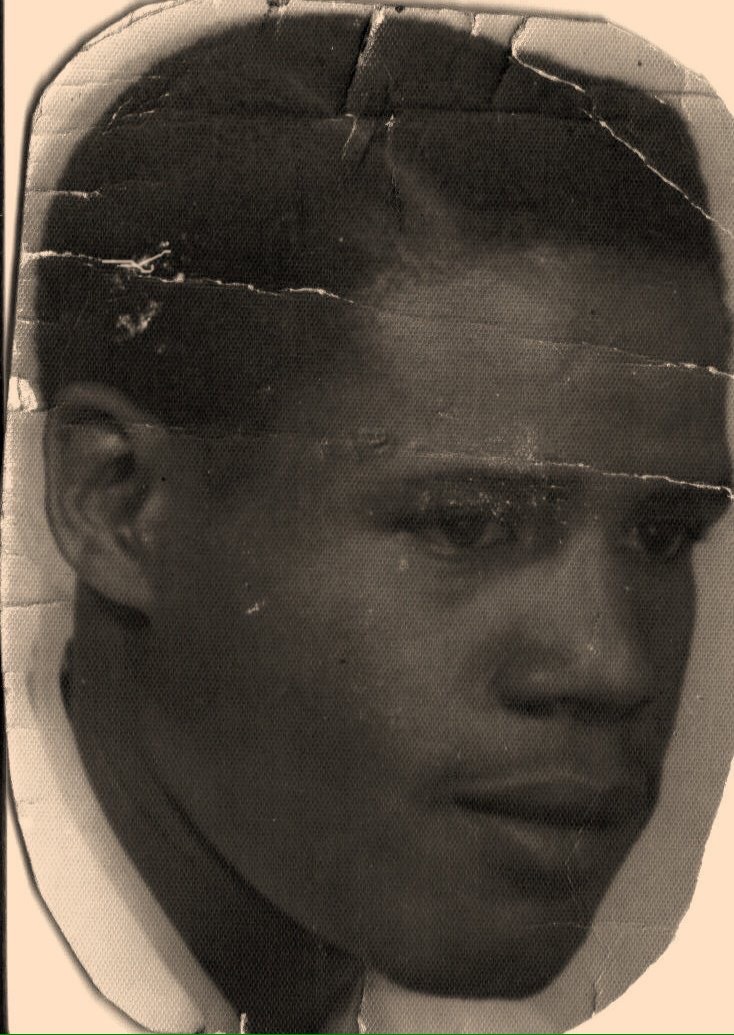

My late father was born in Barbados with a slave holder’s last name. My Grandmothers were all slaves and my Grandfathers were slave-holders. Like many people, I had no distinction in relation to even my own racial identity until I began to learn, as an almost 48-year-old woman, that there are differences – regional, cultural, and linguistic. Adapting a phrase from Anishinaabe-nêhiyaw-Métis critic Janice Acoose, I have come to understand we aren’t one big Black blob. I have the DNA swirls of Taino, and Kalingo women, Indigenous to the Caribbean as well as Brazilian and Guyanese women. I mistakenly thought Guyana was an African country, but it isn’t – it is a South American one – bespeaking further my own ignorance. I still don’t know how to fully describe myself; I usually say I am of “mixed Barbadian ancestry.” There is also the colonial presence within my familial lines, both patrilineal and matrilineal, speaking to the patriarchy and misogyny rooted deep inside the oppression of expansion and the accompanying sexual, often violent, economics.

My Grandfathers on my father’s side were Scandinavian, French, and Jewish. Jewish people held many slaves within the Caribbean context and the Norwegians and Danes were very much a force in colonization, as well. I watched Vikings on Netflix fascinated and slightly obsessed with Ragnar, imagining someone like him falling for one of my Barbadian Grandmothers. I have few oral narratives from my Father; however, he did describe how one of my Grandfathers gave my Grandmother her freedom because he loved her. She even held title to some of the land in Barbados, which was virtually unheard of during the time she existed. I have never been to the territories of my Father’s birthplace; it is the first place I plan on going post-Covid.

On my mama’s side, the colonial presence was slightly different. Many of her Metis relatives had ties to Scotland. Isbisters, Sinclairs, and Camerons on her mom’s side and Harpers and McNabs on her father’s side. The men came, hired as labourers by the British elite, from the Orkney Islands. My Grandmothers were mostly nêhiyaw although our patrilineal family name originally was Meegis instead of Beeds. I traced that sole Grandfather to the Anishinaabe territories of the East. I felt him as I walked along each of the Great Lakes when I took part in the 2015 and 2017 Water Walks led by one of my mentors, role model, and friend Josephine-Ba Mandamin.

Identity is a complex issue and, like so many other Indigenous-Black-Afro-Caribbean people (I am still learning how to describe us in a way that honours our diversity), mine has the added intricacy of double colonialism. I physically “look Black” to many, and yet others “see” the Indigeneity within me. All my life I have felt like I was in a colonial display case, exotic and erotic to some, which turns to a tampering of disgust for others. The violent sexualisation of my brownness occurred early on in life. I began menstruating at age 10. I remember the doctor telling my mother I was going to be “promiscuous” and that I should be on the pill. The same white boys who beat me up as a child continued to bully me into my pre-teen years and they turned into men who used violence, sexually. My Black-Brownness was both loved and hated in this strange dynamic I saw play out again and again in my intimate relationships and in the wider public gaze. It left me confused and marked me with self-hatred and low self-esteem until I found myself and healed those cracks through the Midewiwin society.

As a child, I was fortunate because I did not experience racism from my Cree and Metis relatives. They provided me a shelter from the daily onslaught of settler violence.

I would not have survived if it wasn’t for that unconditional love I found inside the Old people from the communities of Mistawasis, Ahtahkakoop and Mont Nebo. Their love gently wrapped around the bruises, rooting deeply in Cree and Metis teachings of kindness, equality, and respect.

I gained a kôhkom and môsom and an entire extended family when my Late Aunty Shirley married my late Uncle Phillip Ledoux. My mom’s almost-twin sister became a second mother to me and I spent a great deal of time on Misty as a child. The Ledoux family fully embraced me to the point I saw no difference between them and my other blood relatives. I remember after a particularly rough week at school, kôhkom Ledoux wiping my tears and telling me to never let that hurt turn to hate. I know without that little interjection of acceptance, I wouldn’t have survived. My Mide family and other Indigenous people, particularly women who have become sisters and young women who have become nieces, have taken the place of those Old Ones, providing me with that safe space and that unconditional love as an antidote to the racism we collectively face as brown-skinned women and girls.

As an academic scholar of mixed nêhiyaw, Metis, and Barbadian ancestry, I conceptually and theoretically understand racism, but in my heart and spirit, I don’t. How does my skin tone and my racial identity cause others to think I am less than them? It can be subliminal at times, walking in-between two colonially oppressed peoples. Anti-Black sentiment exists in some Indigenous people and anti-Indigenous sentiment exists in some Black people, on top of racism from within the constructs of white supremacy. The racism of one oppressed group towards another has the most painful consequences, even when such racism isn’t fully realized. When I learnt of the Anishinaabe word that emerged or was lost in translation in relation to Black people, I felt that same knot in my stomach as I did on the first day of school when those white kids called me that horrific created name. Even if the original Anishinaabe word or intent wasn’t meant as the word is now, the description has been used and defended by some and, simply put, it is extremely hurtful.

I never want myself or any other Black person, baby, or child to be referred to in such a hurtful and dehumanizing manner that clearly evokes imagery of slavery where our flesh was sold by the pound. Recognizing the oppression of Black people doesn’t have to take away from the oppression experienced by Indigenous people. It isn’t a competition to see who has been traumatized more. Both Indigenous and Black people have been colonially subjugated, but the experience of Blackness is different than the experience of Indigeneity as is other People of Colour’s. One group cannot speak for the other, no matter what, but groups can, and should, support one another, speaking from their own respective identities. Finally, the experiences of being both Indigenous and Black is unlike being one or the other and it gives us a particular type of window.

Ever since I was a little girl, I looked for reflections of myself in my entirety. Not just half of me, but all of me.

There were none.

Coming from the Prairies, I never met another Black-Indigenous person until I moved to Ontario as an adult. The first person I met was a little girl, Aja, who was 6 years old. I remember just feeling an affinity, protection, and love for her. I’m now proud to be one of her Aunties and one of her mama’s good friends. I have met more Black-Indigenous people and, each time, those same feelings emerge simply because of who we are even though, again, it is important to acknowledge our diversity of experiences.

The issue of identity becomes even more complex when our children are born and even more so when our grandchildren are born. My son is of mixed Barbadian, Nêhiyaw, French, and Scottish ancestry. My Barbadian Grandmother was so happy he was not dark because she didn’t want him to have to face the world of racism that she did, not realizing how she was perpetuating that experience. His children, my granddaughters, add German and Polish Romanian to the mix. They are beautifully multi-racial. My eldest has gorgeous red curly hair and blue eyes and my youngest has snapping brown eyes and auburn-brown hair. To look at them, you might not see their Black and Indigenous Ancestors and Ancestresses. They, like their dad, won’t experience the world as I did physically with my brown skin, but my son is my son and they are my grandchildren. I am their brown mom and kôhkom and my love for them is beyond this realm, connecting them to their relatives in the process.

Within most Indigenous cultures and languages, the concept for Ancestral relationality is based on a spiritual understanding of science within an equivalency context. For instance, Nêhiyaw speaker and writer Robin Mcleod articulates how the Nêhiyaw word câpân for “grandparents and grandchildren” articulates the notion of knots in a string. Each generation represents a knot in the same string.[1] I immediately thought of the visual depiction of DNA although the word’s etymology is far older than non-Indigenous science. Within nêhiyawêwin, my granddaughters would use the term “câpân” for my mother and vice versa in recognition of the equal stages of life they are in: beginning and end. McLeod further shares how there are individual words up to the 6th generation because, historically, nêhiyawak would have still been living.[2] The first generation up to the sixth would need words to describe each other. After this point, people generally passed away to became Ancestors, so a single word, nikaskaskâniskotâpân, is used to describe all of them.[3] McLeod explains further how with each generation, the knots became tighter and tighter.[4]

The knots become tighter because our Ancestors are carrying us, their future generations. As a kohkom, I now know what the meaning is behind the Nêhiyaw concept of Ancestry. The first time I held each granddaughter in my arms, I could feel my spirit “knot” to them. Being a mother to my son provided me with that initial tie, but grandchildren are the additional pull with new knots tied to the already formed one. The knots increase and so does the weight of responsibility and obligation when you know you are going to be someone’s direct Ancestor.

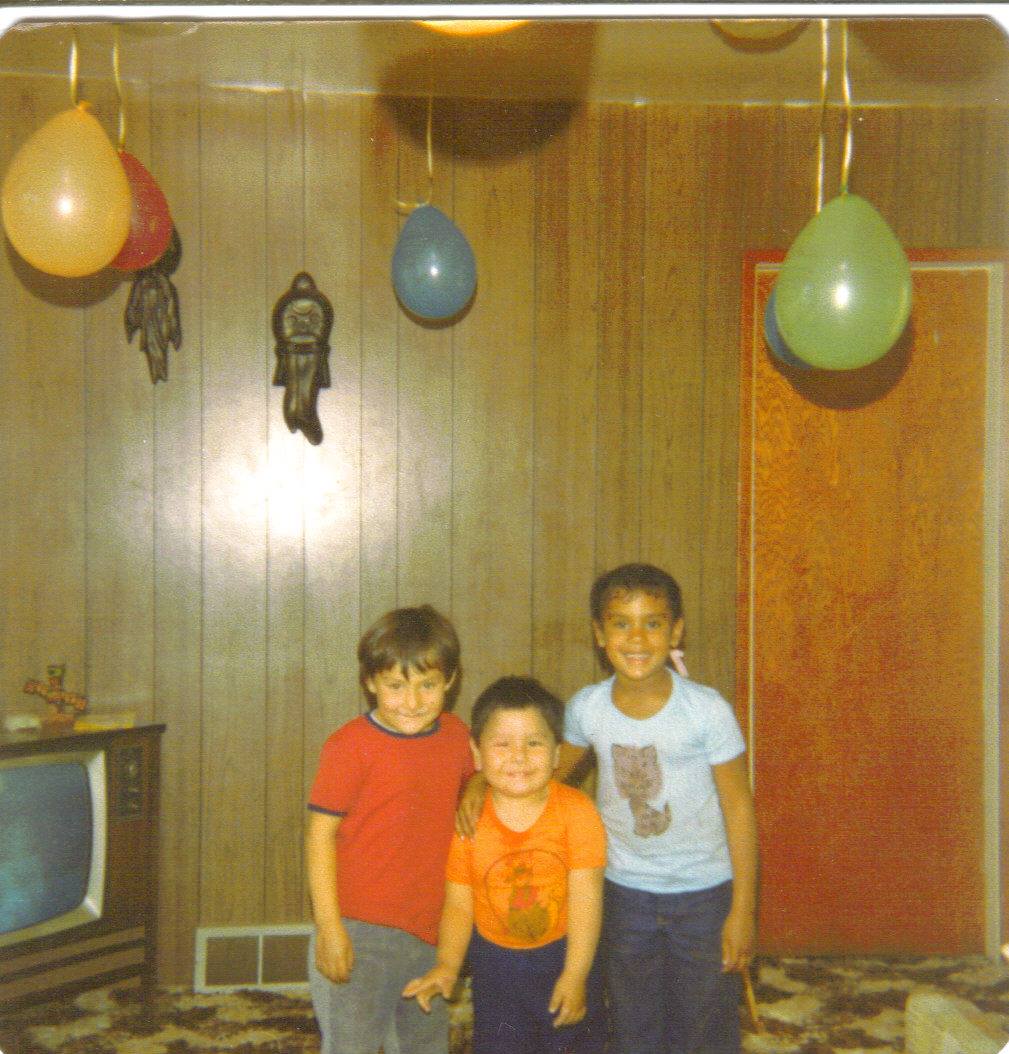

Family… My mom, my late father, son and granddaughters.

It is this responsibility as a kôhkom that drives me in all my actions. Whenever I start to falter, I think of my grandchildren and my great-nieces and nephews. It is for them that I do the work I do and it is for all children that I stand up against inequality and injustice. For me, standing up occurs not only in the context of mass protests, but daily. I confront racism directly when it is safe for me to do so. One day it might be inside the following eyes of a store clerk and the next an experience with institutional racism that demands a formal response like a human rights case. Sometimes, I have no choice, but to walk away for my own survival and well-being. Other times, I draw up my Ancestral shields and go to war. Then, there are the times when all I can do is cry. It is often completely exhausting. I don’t get to put down my brownness when the protests are over – it is a marker of who I am, but I have finally come to a place of self-love and honour. Inside that love is the realization that just as I carry my Ancestors and Ancestresses from the past and my grandchildren into the future, they carry me. I will never again be ashamed of who I am. As a kôhkom, I will continue to stand up, walking when I feel compelled to, and fighting when I have to, for them, for us, and for Creation.

– tasha beeds

[1] See Robin McLeod. 2008. Kinship Wheel: Wahkotiwin.

[2] ibid.

[3] ibid.

[4] ibid.

Tasha Beeds is a professor, a creative artist, a poet, a Water Walker, and Minweyweywigaan Lodge Midewiwin woman.The Midewiwin have roots within the Anishinaabe culture. Compromised of Indigenous people from different Nations, they are a medicine society who utilize Indigenous knowledges, epistemologies, and methodologies to address various social, mental, emotional, and physical issues that impact Indigenous people while actively bringing healing through the realm of spiritual ceremonies. Throughout her academic and community work, Tasha asserts Indigenous ways of knowing and being in the world actively continue to survive colonization, are of tremendous value, and need to be shared to help, not only Indigenous people, but all people as well as the Lands, Waters and entities that rely upon them. She can be contacted via email at nibicreeiskwew2@gmail.com.

Tasha, Thank you! Such a powerful post! Colonial ideas of purity and race are so ingrained in our collective cultures. Too often shaming and violence comes from all sides. And yes, it really does matter when our grandparents teach and protect. And yes, we are dreaming those next generations, and trying to secure a world for them. I like to think that when one person tells a magestic truth, as you have done, it strengthens all of us to be courageous for the generations. Just so you know, I don’t get racism either.

LikeLiked by 1 person

This is awesome Tasha! As someone with a former uncle-in-law from Barbados, I was corrected that the appropriate nomenclature in reference to people from there is “Bajan” (bay-jun). It’s got a better flow than “Barbadian”. I also am connected to increasing numbers of Black/Indigenous peeps and your article had me reflecting on that experience, especially in these BLM times. Be well. xo

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thank you, Tasha.

LikeLiked by 2 people

[…] Walking through worlds carrying ancestral bundles, in the blog tea&bannock […]

LikeLiked by 2 people

Way to go Tash, SO proud of you! SO proud of you!

Love you my friend.

LikeLiked by 1 person